The Roots of National Pride - Should you be proud of your country?

The Roots of National Pride - Should you be proud of your country?

Exploring the Origins and Justifications of Our Patriotism

The Origins of National Pride

As another round of general elections came and went (the third one of my adult life), I was left pondering the concept of national pride, and more specifically, its origins. In any country, national pride transcends political affiliations. But what underpins this deep-seated belief? Do enough of us, in any country in the world, pause to think about the following questions?

- Why am I proud of my country?

- Is the pride justified, and why?

Did I have enough control over the formation of national pride? If not, should I re-evaluate my answer to questions 1 and 2? Let’s start with the first question: Why are we proud of our respective countries? We had no direct part to play in the creation of our countries, or in some cases, in winning their independence. This does not diminish the tremendous accomplishments of the men and women who came before us, but why should we feel proud of them? The same group of fighters liberated both India and Pakistan. Why then should I feel proud of the Indian cohort and not the Pakistani cohort?

The answer is fairly simple: it is because I was born within the geographical boundaries of India, and not Pakistan. This was a circumstance completely out of my control. Why, then, should this foster any sense of pride in my national identity? Surely, a feeling of pride in one’s nation is not a natural, innate emotion. If a child were to grow up without education and isolated from civilization, they would not develop into a proud patriot. Accepting this premise, it becomes reasonably clear that national pride is nurtured, not derived from nature.

At this point, two things are indubitably clear:

- National pride is not natural

- Geographical boundaries, specifically, where you were born, plays some part in instituting that sense of pride

The Arbitrary Nature of Geographic Pride

Let’s dive into the geographic source of national pride. We feel, or are supposed to feel, pride at different geographical hierarchical levels. At first glance, these levels seem highly arbitrary; however, in reality, they are anything but. Let’s use my own identity as an example. Here is a rough breakdown of the geographical hierarchical levels of where I was born:

- Dharampeth (Locality)

- West Nagpur (Urban sub-region)

- Nagpur (City)

- Vidarbha (Geographical/cultural distinction within the state)

- Maharashtra (State)

- Central India (Geographical region within the country)

- India (Country)

- South Asia (Geographical region within the continent)

- Asia (Continent)

- Eastern Hemisphere (Geographical region within the planet)

- The Earth (Planet)

Do I feel pride about each of these hierarchies? The answer is an obvious no. Why should I feel pride about only some of these hierarchical levels and not all of them? Why should I be proud of being an Indian but not a South Asian? Why not be proud of being an Asian? An Earthling? After all, it is my planet as much as India is my country. So why do we feel pride at the seemingly arbitrary geographic boundaries that we do?

Identifying the root cause of geographic pride: A thought experiment

Imagine for a second that Venus, along with Earth, had a habitable population and a flourishing human civilization much like our own. Stretch this imagination further and picture Mars, which is uninhabited but has an abundant supply of water. In this universe, Earth and Venus are at peace with each other, but there is a looming threat of a limited supply of water on both planets, with the water on Mars within reach. I am willing to bet good money that “Earth Pride” would be an ingrained concept among Earth’s population in this fictional universe. After all, if this pride did not exist, who would fight for the planet in a potential war with Venus?

This scenario illustrates why pride exists (or, as I believe, is nurtured) at specific hierarchical levels. There is no “North American” pride because North America is not competing with the South for resources, but the United States and Mexico are competing for resources within North America. Similarly, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka do not form a collective “South Asian” pride because we are not competing for resources against the rest of Asia, nor are we sharing our resources with one another; instead, we are competing against each other.

We observe similar developments within a nation’s borders. Why does Maharashtra pride exist? Because we compete with other states for resources (think of the Maharashtra-Bihar rivalry over the limited number of government jobs, a resource to fight over). Of course, we unite against a greater common threat, but in the meantime, the formation of state-level pride occurs. Likewise, in the aforementioned thought experiment, even if Earth were to unite against Venus, we would still see a sense of national pride prevalent in all countries.

After this thought experiment, the geographical levels at which we feel pride do not seem quite as arbitrary. This is why no one campaigns for “West Nagpur” pride; resources within Nagpur are distributed within the geographical regions of the city without much competition, if any. The pattern becomes clear: pride is often invoked at any geographical level where there is a perceived threat to one’s existence or way of life, often due to a scarcity of resources.

The Influence of Education

So far, we’ve established that pride is nurtured at specific hierarchical levels. What we still have to discuss, is how it is nurtured. Naturally, your family, upbringing, and culture play a very significant role in the development of this pride. There are other channels that play a role too, such as mass media, movies, government influence, etc. However, the most crucial role, perhaps, is played by education. Everyone remembers the school assemblies, with the national anthems, the pledge, and all other activities that foster a sense of national pride, and help to develop a sense of national identity. Diving deeper, it is obvious that educational curriculums are also designed to inculcate this sense of pride within us. Stories of our independence, of our martyrs, of our heroes are scattered throughout our history lessons. These stories, and narratives are fed to us in our formative years, which contributes to a strong sense of national pride.

I have a hypothesis that I would love to test, on just how influential education is in the formation of pride, at not just the national level, but also the regional levels. I grew up in Nagpur, studying the Maharashtra State board curriculum, rather than the CBSE curriculum. I am extremely confident in my belief that a sense of regional pride, or having a sense of identity as a Maharashtrian, is much stronger in students who studied the Maharashtra state board over the CBSE board. In an ideal world, I would love to run a controlled social experiment to measure this difference in a target group vs a control group. Given all other factors being the same (Familial influence, mass media influence, etc.), I am confident that such an experiment would prove my hypothesis correct.

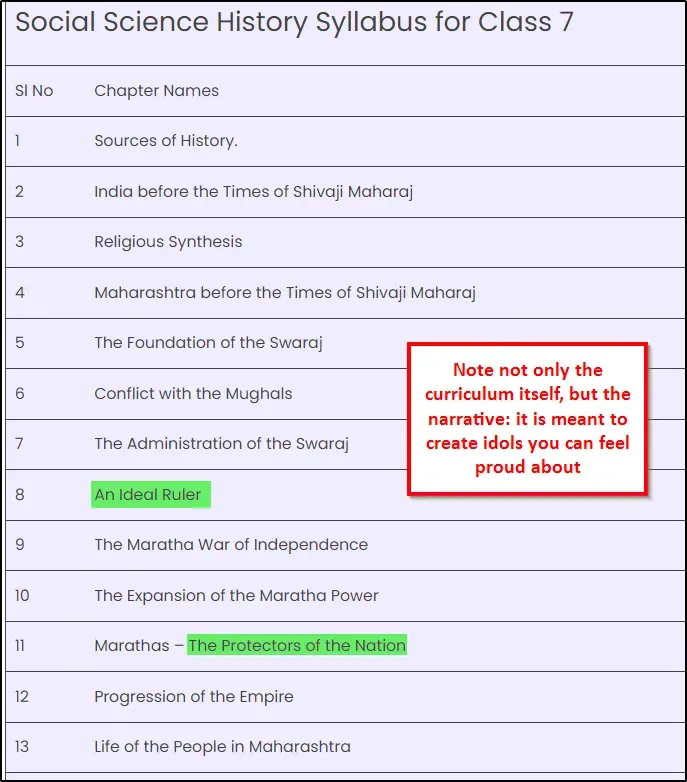

Consider the Maharashtra State board’s curriculum for 7th grade history:

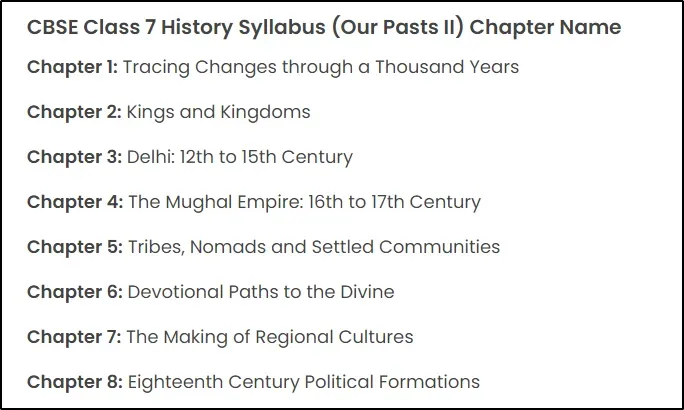

Maharashtra State Board 7th Grade History Curriculum Contrast it versus the CBSE curriculum:

CBSE 7th Grade History Curriculum

Conclusion

Naturally, there are other factors that contribute to this sense of pride as well — when our sports teams perform well, or when we collectively achieve something commendable, like the Chandrayaan mission. However, my primary interest lies in exploring the origins of this pride, examining when it first takes root, and identifying the levels at which it forms. This analysis could be much deeper and more rigorous, yet even at this level of depth, I want to revisit the two questions I posed at the beginning of this article.

Why am I proud of my country? Because I was raised to be. Is the pride justified, and why? If my pride stems solely from these factors and not from a critical evaluation of my country’s merits, then no, it is not justified. I should delve deeper to understand whether my country deserves my patriotism and conclude whether or not I should be proud of it.

If each of us tries to answer these questions, we might move beyond the empty platitudes ingrained in people across all countries — “China numba wan!”, “America is the best country in the goddamn world!”, “Mera Bharat Mahan!” — and actually support our countries (or not) for valid reasons. Screw JFK; do ask what your country can do for you. We might actually become global citizens who care about humanity in general and refuse to defend our countries’ actions when they are indefensible.

Of course, this idealistic scenario is unlikely. As illustrated in the thought experiment, national pride is essential for the survival of the nation. No governing body will leave any stone unturned in ensuring that this pride is deeply ingrained from a young age.